Forty Years @ 24 Frames Per Second: Film Cooperatives in Canada

Essay by Penny McCann

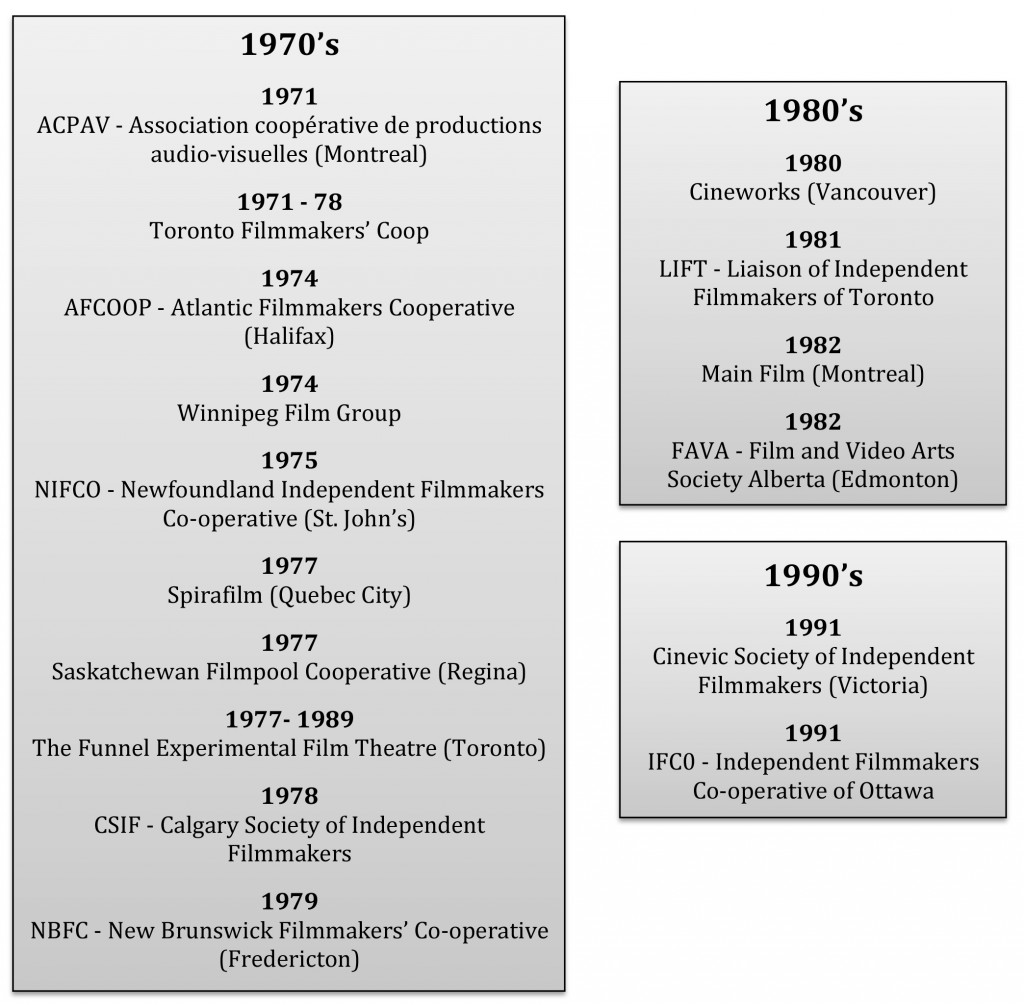

Forty years ago in 1975, video was in its infancy, celluloid was the industrial standard and independent filmmakers struggled to find the equipment, facilities and resources to create films outside the mainstream. To meet this necessity, three filmmaking cooperatives had been newly formed: ACPAV (Association coopérative de productions audio-visuelles) in Montreal, the Atlantic Filmmakers’ Cooperative in Halifax, and the Winnipeg Film Group. [i]

AFCOOP’s founding story sets the scene. In 1973, 17 artists gathered at the Seahorse Tavern in Halifax to chat about filmmaking. According to AFCOOP’s website: “The conversation flowed and someone came up with the idea of establishing a filmmakers’ co-operative in Halifax. Thanks to the dedication of these 17 filmmakers, and initial funding provided by the Canada Council for the Arts, the Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative was incorporated a year later on June 3rd, 1974.”

The Winnipeg Film Group formed as a direct result of the Canadian Film Symposium at the University of Manitoba, an annual event held to screen and discuss independent Canadian films and filmmaking. During this symposium, several local independent filmmakers banded together to approach the government to assist with funding to form the Winnipeg Film Group in 1974. [ii]

Funding from the Canada Council for the Arts was instrumental in creating the conditions for film cooperatives to develop. Françoyse Picard, who became the Canada Council film officer in 1975, offers insight into the key role the Canada Council played in supporting film coops.

“When I arrived at the Canada Council in 1975, there were three co-ops getting funding, some centres were folding, and the CFDC [Canadian Film Development Corporation, Telefilm’s name until 1984] wanted to [take] film funding back from the Council. We wanted to fund auteurs, film directors, and not necessarily the centres of production in Toronto and Montreal that the CFDC was identifying. We feared that the government would say no for funding film at the Canada Council, and wondered what could we do to be distinct?”[iii]

What the Canada Council did was to support the creation of film cooperatives, resulting in centres springing up across the country.

The impact of film cooperatives on Canadian film culture is undeniable but not easily quantifiable. Thousands of films of various lengths have been made at film centres over the past four decades. Access to grants, equipment, mentorship, willing hands, as well as distribution and exhibition networks helped form many established Canadian filmmakers. For some, the centres provided an entry into the film and television industry; for others, they facilitated and continue to facilitate the freedom to work independently and/or in opposition to the industry.

Cameron Bailey acknowledges the impact and influence of cooperatives on the establishment of the Toronto New Wave in the 1980’s:

“When [Bruce] McDonald helped form the Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto (LIFT) in 1980, it gave a home to an artisanal method of making films that had no place at the NFB or under any tax shelter. LIFT became a church for the gospel of do-it-yourself. Edit it yourself. Learn to run the Arri and shoot it yourself. Better yet, get a Bolex. McDonald’s early shorts Knock, Knock and Let Me See … motor along on DIY bravado…. It was through LIFT that young wannabes could become complete filmmakers. They could gain control.”[iv]

Now, 40 years later, celluloid has diminished to the point of near extinction and still the centres remain, secured by Canada Council funding and negotiating a path strewn with the wreckage of obsolete technology. Nine years ago, I participated in LIFT’s 25th anniversary commissioning program, Film is Dead…Long Live Film. Then, as the title of the programme attests, the writing was on the wall for film. Now, the wall is almost completely gone, taken apart brick by brick as industrial support for celluloid literally vanishes. With fewer and fewer film schools engaging with film technology, celluloid production is now a rarefied act and film coops the monasteries in which the devotees toil. Film is now almost entirely a production medium for experimental media artists. DIY processes and expanded cinema practices now find a home at many centres. Akin to the illuminated texts of the Irish monasteries during the Dark Ages, material filmmaking persists in conditions of diminishing expectations.

A review of programming in 2014 reveals that commitment to celluloid remains an important aspect of most film centres. For instance, four centres, LIFT, the Winnipeg Film Group, Main Film, and Cineworks offer access to darkrooms to support hand-processing; Vancouver’s Cineworks has created a DIY studio space called the Annex to support celluloid practices; and LIFT provides comprehensive training and access to film equipment at a level that has been relinquished by most film schools in Canada, as well as access to film stock and supplies through its popular LIFT Store. In Ottawa, IFCO maintains a commitment to shooting on film only, hosts a 16mm training program for women and has plans to build a darkroom. Around the country film challenges are a key strategy used to spark and retain interest in celluloid; in 2014, eight centres hosted Super 8 or 16mm challenges or commissioning projects. Artist residencies are offered by AFCOOP and LIFT, providing opportunities for artists to make works on film while mentoring others in the community. Other centres offer master classes and hands-on workshops. Main Film in Montreal promotes a research/creation opportunity to artists through its Film Factory granting program and the Calgary Society of Independent Filmmakers keeps celluloid exhibition alive with its $100 Film Festival, one of only a few festivals in the world that showcases film exclusively on Super 8 and 16mm. Other media art centres have also embraced film production to differing degrees: the Island Media Arts Cooperation in Charlottetown, PEI and the Yukon Film Society in Whitehorse provides rental access to 16mm and Super 8mm cameras; Faucet Media Arts Centre in Sackville, New Brunswick, and MediaNet in Victoria provide access to film cameras as well as offering Super 8 production and hand-processing workshops.

Any review of current activities at film production centres includes the use of digital technology within the broader definition of filmmaking, a term that is now routinely used to describe digital works. To meet the needs of aspiring and established filmmakers in their regions, the majority of centres have responded by investing in high-quality digital cinema equipment. And so film cooperatives have come back full circle. Their raison d’être remains as it was 40 years ago, to support the independent filmmaker seeking to make work outside the commercial or industrial model. With very few exceptions, the film cooperatives offer independent filmmakers the equipment they require, regardless of the choice of medium.

And therein lies the key to the future of film cooperatives in Canada. Initiated as places of creation, dissemination and inspiration decades ago, those centres that remain vital and responsive to the filmmakers in their communities will be the ones that survive, whether as sites for artisanal and DIY filmmaking, preserving the increasingly rare tools of celluloid production or as facilitators of equitable access to the tools of digital filmmaking. And just as the Canada Council set the stage for the establishment of film cooperatives 40 years ago, so it will again be the arbiter of which centres moves forward into the future.

[i] Although the term “cooperative” is commonly used to describe Canadian film production centres, not all centres are legally constituted cooperatives.

[ii] Winnipeg Film Group website.

[iii] Peter Sandmark, Independent Media Arts in Canada: On the History of the Alliance (Independent Media Arts Alliance, 2007), p. 15.

[iv] Cameron Bailey, Standing in the kitchen all night: a secret history of the Toronto new wave, TAKE ONE, Summer, 2000.

Bio: Penny McCann is an established media artist who makes both narrative and experimental films and videos. Her work has been exhibited widely at festivals and galleries nationally and internationally. Currently Director of SAW Video in Ottawa, Penny has participated in and contributed to the national media arts scene for over two decades, most notably serving as national president of the Independent Film and Video Alliance (now IMAA) from 1996-1999. In 2014, in recognition of her contribution to artist-run centres in Ontario, Penny was awarded the ARCCO Achievement Award. Penny currently serves as Chair of the Media Arts Network of Ontario (MANO).